At fourteen, I longed for the “pretty…country girl,” whoever she might be.

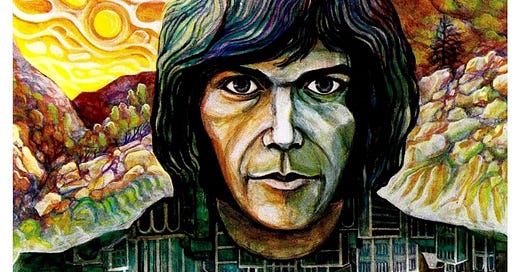

Though maybe I had heard his name somewhere before, it was CSNY’s 1970 LP Deja Vu that first brought Neil Young to my attention. I was only fourteen then, and part of me questions, “What did I really know about music?” While another part understands, “but the song on Deja Vu you loved above all others was Neil’s “Country Girl Suite,” not a piece that drew heavy-loving fandom. Sure, the hits—“Teach Your Children,” “Our House,” and “Woodstock”—coaxed me in, but how often did I pick up my tonearm and set it right back down so that I could mourn through the loss again of the “waitresses paying the price of their winking.” At fourteen, I longed for the “pretty…country girl,” whoever she might be.

So that song, really, set me on the Neil Young journey. As soon as I could mow another lawn, I bought After the Gold Rush.

Then Harvest was released, and it was only after this that I chose to spend my money on Young’s first record, the self-titled debut (just as an aside, my friend Don bought me Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, Young’s second LP, and I’ll never know why he was so gracious, since Don pretty much hated Neil Young’s music).

Young’s debut album appeared in 1968, just after he split with Buffalo Springfield, a band I knew of but couldn’t have distinguished when it was alive from The Byrds, The Yardbirds, or even Strawberry Alarm Clock.

Springfield once appeared on ABC’s late Saturday night variety series, The Hollywood Palace, which aired at 10:30 Birmingham time. I remember these details even though I was not allowed to stay up that late, much less to watch an obscure rock band sing about men with guns telling others that they “got to beware.”

So when I finally bought Neil Young, I was fifteen or sixteen and of course ready to understand the complexity of his first solo sounds.

What I mean to say is that I understood nothing except for the rarity of a voice that sang about subjects I hadn’t quite considered before. The album’s most well-known song, “The Loner,” carries on Young’s themed persona from such Buffalo Springfield songs as “Broken Arrow” and “Mr. Soul.” Aloof figures who “drop by to pick up a reason.” So many words in “The Loner,” though, had me reeling and believing that Young might be both the strangest and the most romantic rock singer I had ever heard:

There was a woman he knew about a year or so ago.

She had something that he needed and he pleaded with her not to go.

On the day that she left,

He died,

But it did not show…

It all felt like that for me, too, through the Mary Janes and the Melissas and even the Robyns and Connies who never noticed me. I felt I died a little every time we passed and they were looking at someone else.

The album swings wildly through forms and genres and moods. There’s certainly a country lilt right at the beginning with the instrumental, “The Emperor of Wyoming,” and anyone who knew anything about Young understood that the American West, both in mythology and reality, drew Young like a teenage boy to a record store. ”Emperor” leads right into “The Loner,” which isn’t so jarring because country and rock would be walking together even more often in the years to follow.

From there, the song sequencing goes sideways.

“If I Could Have Her Tonight” is a steady beat lamentation that I didn’t know how to place and always worried that someone—like Don or one of my other hard rock friends—would catch me listening to and then have to start a fund drive for my manhood.

But the next track is “I’ve Been Waiting For You,” whose heavy guitar chords seem to refocus us onto the heart of the rock sound. So, as I first listened, I figured that would be it, and Young, while maybe throwing another ballad into the mix, would pretty much take me through a guitar-droned set.

The next song, however, is “The Old Laughing Lady.” According to his memories, and Wikipedia, and his biography, Waging Heavy Peace, the song was written on a napkin in a coffee house while Young was waiting for the part of the band’s car that was stolen to be returned. Or something like that. It’s hardly a song you’d think of, much less write, while living through such a seemingly slapstick encounter, though:

There’s a fever on the freeway, blacks out the night.

There’s a slipping on the stairway, just don’t feel right.

And there’s a rumbling in the bedroom and a flashing of light.

There’s the old laughing lady, everything is all right.

I remember trying to dissect those lyrics for a song analysis in my 11th-grade English class (not bad for an Alabama public high school). I saw the old laughing lady as a variety of metaphors (the bottle, lost love), but now, I see only the fever on the freeway, hear only the rumbling in the bedroom, and of course, everything isn’t all right. Maybe that’s just my age talking, but images will transform through the years.

Which brings me to side two and the only song I really want to mention—the only other song that shocked and riveted me back when I first listened to the record on a portable hi-fi system in my bedroom—the bedroom I inherited from the old laughing lady who was my maternal grandmother—a very precious woman to and toward me.

When I finally saw Neil live in concert, in Tuscaloosa in the spring of ’72, he opened with this song, maybe the most unexpected concert move I ever experienced, short of Uriah Heep canceling after the opening band— Earth Wind and Fire—had already ended their set. The song, like many of the others on the LP is just over two minutes long: “Here We Are in the Years.”

It starts as such a pretty song and then as it builds, its images flash from “the slower things that the country brings” to “time itself,” my mortal enemy, allowing more concrete and steel to overwhelm the pastoral villages and so on.

So the subtle face is a loser, this time around…

here we are in the years, where…

children cry in fear, let us out of here.

I couldn’t go on listening this first time around, and after I finally heard Springfield’s farewell album, Last Time Around, I got it. Saying farewell to what you knew, what you were, and all the hard work making it, only to start again, to start fresh.

Back in those years, I wanted so badly to find someone to talk to about this song, this album. I didn’t quite abandon such thoughts, and so, while the years have definitely passed, here we are, finding moments to see and hear them all again: to listen to an album that maybe was too far ahead of itself, or, perhaps, already too far gone.