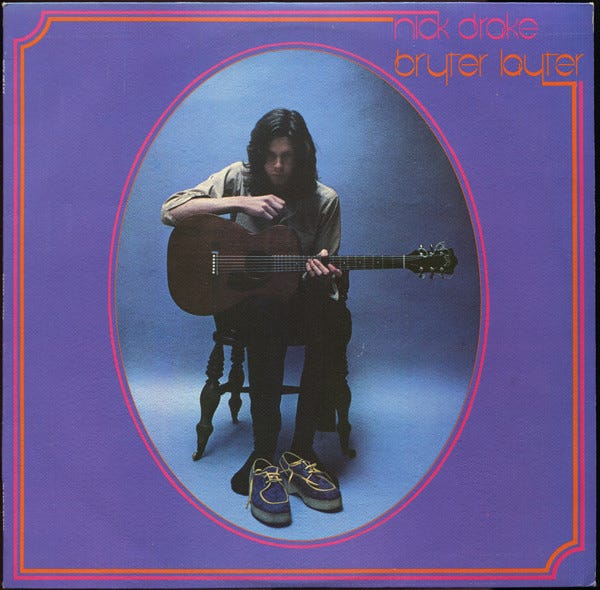

Nick Drake — Bryter Layter

23.July.2020

Nick Drake

Bryter Layter

1970

In looking at Nick Drake’s oeuvre, conventional wisdom would point to looking at either his first album, Five Leaves Left, or his last studio recording, Pink Moon.

Naturally, I selected neither.

Often overlooked is the middle child album, 1970’s Bryter Layter.

After the antagonistic indifference that met his debut, Five Leaves Left, Englishman Drake returned to the studio with producer ex-pat American Joe Boyd.

Where Five Leaves Left is notable for its sparse instrumentation and Drake’s solo approach, Bryter Layter is the opposite.

There are brass instruments and lush string arrangements — all by Robert Kirby — who would go on to work with Elton John, Paul Weller, and Elvis Costello, among others.

There are drums — played by Beach Boy drummer Mike Kowalski and Fairport Convention drummer Dave Mattacks.

There are collaborations — most notably, Richard Thompson (lead guitar on “Hazy Jane II”), and The Velvet Underground’s John Cale (viola and harpsichord on “Fly” and celeste, piano and organ on “Northern Sky”)

There are backing vocals — by P.P. Arnold from the Ike & Tina Turner Revue and Doris Troy, one of the background singers on Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon.

It was a solid attempt by both Nick Drake and Joe Boyd to score a hit album. To be blunt, Bryter Layter was getting after it.

The songs on Five Leaves Left, largely written while Drake was attending Cambridge University, were singular and atmospheric — in a British folk music kind of way. The songs on Bryter Layter were written while he was living in London and are beefy and muscular — in a British folk music kind of way.

By 1970, folk music was moving away from the branding that identified people like Pete Seeger and early the pre-electric Bob Dylan, and adopting the less politically associated branding of “singer/songwriter.” And because of this artists were making successful forays into pop music.

Simon and Garfunkel had pierced the pop market with their brand of ‘pop-folk” with Bookends in 1968 and in January of 1970, they released the watershed album Bridge Over Troubled Water, reaching #1 on the Billboard Album Chart.

In February, James Taylor released his album Sweet Baby James, which made it to #3 on the Billboard Album Chart and contained the hit “Fire and Rain”.

That was the audience Drake and Boyd were going after on this sophomore album. Unfortunately, Nick Drake had more than just his overt Englishness working against him … he had a touch of melancholy. Bryter Layter can almost be read as a resignation that it will get better … later.

Despite the softness of his voice and the beautiful string arrangements on the album, there is an Englishness to it that goes just a little deeper than being just your run of the mill “bummer” record.

A song like “At the Chime of a City Clock” is just one of them. Writer David Hepworth said the song was “the perfect soundtrack for the dispensing of a cup of tea in a polystyrene cup, marrying sound and image in a way that made me unsure whether I was watching a commercial or actually in a commercial.”

Very British, but the song isn’t your traditional British cynicism. The lyrics indicate a darker side … and it’s not the kind of melancholy that appeals to most people:

At the Chime of a City Clock

A city freeze

Get on your knees

Pray for warmth and green paper.

A city drought

You’re down and out

See your trousers don’t taper.

Saddle up

Kick your feet

Ride the range of a London street

Travel to a local plane

Turn around and come back again.

And at the chime of the city clock

Put up your roadblock

Hang on to your crown.

For a stone in a tin can

Is wealth to the city man

Who leaves his armor down.

Stay indoors

Beneath the floors

Talk with neighbors only.

The games you play

Make people say

You’re either weird or lonely.

A city star

Won’t shine too far

On account of the way you are

And the beads

Around your face

Make you sure to fit back in place.

And at the beat of the city drum

See how your friends come in twos;

Or threes or more.

For the sound of a busy place

Is fine for a pretty face

Who knows what a face is for.

The city clown

Will soon fall down

Without a face to hide in.

And he will lose

If he won’t choose

The one he may confide in.

Sonny boy

With smokes for sale

Went to ground with a face so pale

And never heard

About the change

Showed his hand and fell out of range.

In the light of a city square

Find out the face that’s fair

Keep it by your side.

When the light of the city falls

You fly to the city walls

Take off with your bride.

But at the chime of a city clock

Put up your roadblock

Hang on to your crown.

For a stone in a tin can

Is wealth to the city man

Who leaves his armor down.

It would take years for people to understand the beauty and lyricism of Drake’s songs.

Even his love songs had a dark undercurrent of torment to them. “Hazey Jane I” and “Hazey Jane II”, curiously sequenced out of order on the album — tracks 5 and 2 respectively — seem to portray a kind of ill-fated love. Which is a well-trafficked topic for pop music … but in these songs, there is a haunting sadness or even doom to them.

Hazey Jane I

Do you curse where you come from,

Do you swear in the night

Will it mean much to you

If I treat you right.

Do you like what you’re doing,

Would you do it some more

Or will you stop once and wonder

What you’re doing it for.

Hey slow Jane, make sense

Slow, slow, Jane, cross the fence.

Do you feel like a remnant

Of something that’s past

Do you find things are moving

Just a little too fast.

Do you hope to find new ways

Of quenching your thirst,

Do you hope to find new ways

Of doing better than your worst.

Hey slow Jane, let me prove

Slow, slow Jane, we’re on the move.

Do it for you,

Sure that you would do the same for me one day.

So try to be true,

Even if it’s only in your hazey way.

Can you tell if you’re moving

With no mirror to see,

If you’re just riding a new man

Looks a little like me.

Is it all so confusing,

Is it hard to believe

When the winter is coming

Can you sign up and leave.

Hey slow Jane, live your lie

Slow, slow jane, fly on by.

But all is not doom and gloom on Bryter Layter. There is a full-on love song!

“Northern Sky”, marks one of Drakes’s two collaborations with John Cale. While the album is a break from Drake’s music, this song marks a real turn for Drake. This would be the best example of how Drake and Boyd were “getting after it” and trying to create a hit song. Writer Peter Pahidies said it was “the most unabashedly joyful song in his canon.”

Northern Sky

I never felt magic crazy as this

I never saw moons knew the meaning of the sea

I never held emotion in the palm of my hand

Or felt sweet breezes in the top of a tree

But now you’re here

Brighten my northern sky.

I’ve been a long time that I’m waiting

Been a long that I’m blown

I’ve been a long time that I’ve wandered

Through the people I have known

Oh, if you would and you could

Straighten my new mind’s eye.

Would you love me for my money

Would you love me for my head

Would you love me through the winter

Would you love me ’til I’m dead

Oh, if you would and you could

Come blow your horn on high.

I never felt magic crazy as this

I never saw moons knew the meaning of the sea

I never held emotion in the palm of my hand

Or felt sweet breezes in the top of a tree

But now you’re here

Brighten my northern sky.

“Northern Sky” was one of the songs that opened the floodgates on the discovery of Nick Drake’s music that began to take shape in the early 80s. At the time just critic darlings R.E.M. went after Joe Boyd and enlisted him to produce their third album — Fables of the Reconstruction, also known as Reconstruction of the Fables — in 1985.

And the hit single “Life in a Northern Town” by The Dream Academy was based on and inspired by “Northern Sky”.

However, Drake’s label Island Records didn’t choose it as a single in 1970, and that, combined with their lack of marketing support for Bryter Layter meant that the album was not going to see brighter days.

Regrettably, neither was Nick Drake.

CRITICS:

Andrew Means in his original review from Melody Maker in 1971 said: “The tracks are all very similar — quiet, gentle and relaxing. Nick Drake sends his voice skimming smoothly over the backing.”

Jayson Greene at Pitchfork said: “this is the Nick Drake you can hear reflected in latter-period Belle and Sebastian. He rehearsed with a band for the first time, including other members of Fairport Convention, and the result is the most fulsome studio recording he ever managed.”

Q placed Bryter Layter at number 23 in its list of the “100 Greatest British Albums Ever”.

NME’s ranked it #14 on their list of “The Greatest Albums of the ‘70s”.

Rolling Stone Magazine ranked Bryter Layter # 245 on their list of The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.

Much has been made of Nick Drake’s use of marijuana — I don’t know, maybe weed was different back then, but that hardly seems the source of his moody demeanor and behavior. While there is some speculation that John Cale may have introduced him to heroin during the Bryter Layter sessions, there is no evidence of that.

In any case, Nick Drake would eventually be treated for depression and prescribed amitriptyline. Whether it was accidental or deliberate, Nick Drake died in December of 1974 as a result of what the coroner said was: “Acute amitriptyline poisoning — self-administered when suffering from a depressive illness” or suicide.

Although that remains disputed. There was no suicide note, only a letter to friend Sophia Ryde on his night table. Most interestingly, producer Joe Boyd claimed that his parents had reported a positive mood and he had been vocal about moving back to London to restart his music career.

Boyd believes that Drake may have had a positive “high” followed by a “crash back into despair” and he goes on to reason that Drake may have:

“Taken a high dosage of antidepressants to recapture this sense of optimism making a desperate lunge for life rather than a calculated surrender to death.”

In any event, it is only Nick Drake’s music that lives on … and we should be thankful for that.

Perhaps Bryter Layter was more predictive than initially believed. It did get brighter … it’s just that Nick Drake wasn’t around to see it.

A tragedy that one man’s pain ended up eventually being everyone else’s pleasure.