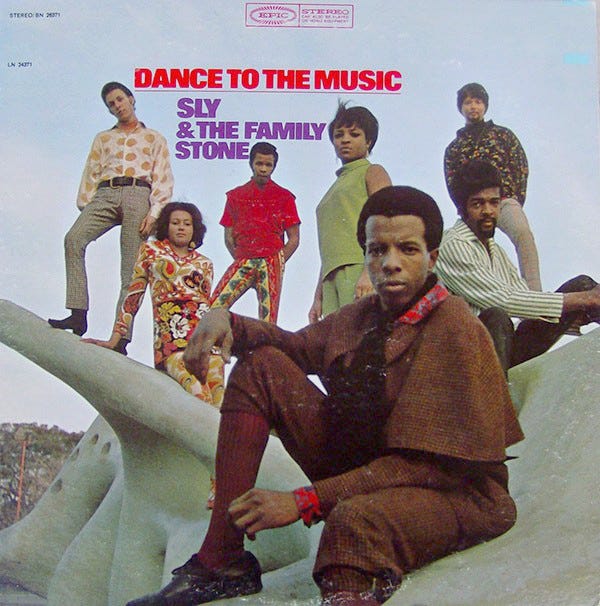

Sly & The Family Stone — Dance to the Music

June.2.2020

Sly & The Family Stone

Dance to the Music

1968

I was never in the Armed Forces so “Dance to the Music” is the only command I don’t mind having barked at me.

But, to be fair, it’s the only thing the song is asking me to do, so it’s not too much … and Sly & the Family Stone couldn’t be more joyous in their tone so it’s impossible not to oblige.

Clive Davis, head of Epic Records in 1968, is known for many things, chief among them is knowing what works for an artist and what doesn’t.

In 1968, he was at the peak of his powers and for their second album, Davis felt Sly & the Family Stone needed a more pop-friendly sound to reach a wider audience.

So The Family Stone and in particular Sly set about creating an original sound that would combine Sly’s vision of peace, brotherly love, and anti-racism. In 1968 to try and have the artistic and intellectual bandwidth to maintain your integrity, appease the boss, your race, bandmates, and gain career traction was no small task … well, it still isn’t (it’s just that now, considerably less of that is left to the artist.)

The album Dance to the Music was the resulting product — a mashup of R&B/funk/soul/pop/rock and a dash of psychedelia (given the era) branded “psychedelic soul.”

Sly & the Family Stone shaped “psychedelic soul” on Dance to the Music by having the four lead singers — Sly Stone, Freddie Stone, Larry Graham, Rose Stone — singing together or alternating on each verse. The songs on Dance to the Music also contain a fair amount of “scatting” mixed with prominent solos for the instrumentalists.

Not a complicated formula, but it works. On the one hand, the album sounds like an extended jam or rehearsal. In particular the first four songs:

“Dance to the Music”

“Higher”

“I Ain’t Got Nobody (For Real)”

Dance Medley — “Music is Alive”, “Dance In”, “Music Lover”

And on the other hand, well, it’s an extended jam that when songs like “Ride the Rhythm” kick in, you’re already riding the rhythm — making the band’s request redundant.

Slowing the groove on “Color Me True” Sly tackles the larger existential question about where or how one even fits into society:

Color Me True

Are you earning all of your money?

Do you laugh at the boss’s jokes when they are funny?

Color me true

Do you know what makes you tick?

Do you know how to avoid what makes you sick?

You might think and talk just like a player

Would you know how to talk to your city mayor?

Color me true

Do you take credit for somebody else’s cooking?

Do you look at the park when you think nobody’s looking?

Color me true

Do you know how to treat your brother?

Do y’all know how to get along with one another?

When you retire, do you go right to sleep?

Do toss and turn when fear starts to creep?

Color me true

The song “Higher” contained here on Dance to the Music would later be reworked into the version we know as the hit (and much better) “I Want to Take You Higher” … and you’ll hear bits of what ended up on that version all over on different songs here on Dance to the Music.

Lyrically the album isn’t complex but since when is it necessary to have complex wordplay to deliver a message (see above lyrics)?

The band itself never thought too much of Dance to the Music but that’s moot for three reasons:

Sly’s message of peace, brotherly love, and anti-racism are embedded here not just in his mixed race and gender band but in his songs.

Both the single “Dance to the Music” and the album became hits.

Producers and other labels began appropriating Sly & the Family Stone’s newfound “psychedelic soul” sound and soon The Temptations, Four Tops, and upstarts The Jackson 5 take a stab at it … with varying degrees of success.

Critics were mixed at the time and remained mixed on reissues in the mid-’90s:

Rolling Stone called it “uneven”.

AllMusic referred to it as “Bursting with joy and invention” but “not a perfect record”.

The now-bankrupt Tower Records, in their magazine, somehow felt compelled to award it three stars without reviewing the music and simply making personal judgments on Sly Stone.

Only the U.K.’s Q Magazine spoke highly of the record saying that it was on this album that “pure electricity transposed to vinyl” and that the band “truly coalesced with the miraculous title track featuring Larry Graham’s mastodon-on-a-rampage bassline” and that “Dance to the Music anticipates Miles Davis’ experiments with Teo Macero.”

Listening today, you may think: “What’s the big deal?”

That’s hard to explain. Everything has changed so much. I wasn’t alive when the record was released but can still place it in a historical context.

Lyrically and sonically, no, Dance to the Music isn’t revolutionary.

But sometimes revolution isn’t about new sounds OR messages. It’s about resonating with people and in 1968, that was critical … in particular to Sly Stone. So he created a mixed-race, mixed-gender rock/funk band preaching peace and love — admittedly, that was the message de rigueur, but the race and gender was a twist. And Sly did it at one of the most tumultuous and divisive times in recent history.

That WAS revolutionary.

And then Sly & the Family Stone drop an album that not only deliver songs that are joyous romps like the title track but also tackle larger themes like your place in life “Color Me True” and cultural strife like “Are You Ready” and “Don’t Burn Baby Burn”:

Are You Ready?

Don’t hate the black

Don’t hate the white

If you get bit

Just hate the bite

Make sure your heart is beatin’ right

Don’t Burn Baby Burn

I can understand frustration

Joined by agitation

Creates aggravation

Led by a congregation

But don’t burn baby, burn

You just learn, baby, learn

Don’t burn baby, burn

You just learn, baby

These songs had a simple intellectual resonance, but larger cultural one that transcended all barriers in 1968 … and still do in 2020 … in particular at this very moment.

Turns out Clive Davis was right, Sly & the Family Stone did need a more pop-friendly sound. Turns out, so did America.

I just don’t think Clive or anyone, maybe even Sly himself, expected something of the quality and depth of Dance to the Music.